Brazilian Nail-Biter

A left-wing lightning rod and far-right firebrand face off in Brazil’s upcoming runoff.

Read

Pollsters in Brazil had Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the comeback candidate, leading by as many as 14 percentage points in the presidential election. But neither top nominee won a majority this month, sending citizens back to the polls for a historic runoff. And democracy itself is on the line. Incumbent president Jair Bolsonaro has waged war on reality, sowed division on social media and attacked the press. We check in with one of his targets, journalist Patrícia Campos Mello, ahead of the Oct. 30 rematch.

Trailing throughout the campaign, Bolsonaro finished with a stronger-than-expected 43 percent, 5 points behind da Silva — known in Brazil simply as “Lula.” In a move all too familiar to U.S. voters, Bolsonaro has been attacking the country’s election system, especially electronic voting machines, without evidence. Campos Mello says she fears the potential of “January Sixth times ten” if Bolsonaro is defeated in the second round but refuses to concede.

Key to Bolsonaro’s disinformation strategy, Campos Mello says, is maintaining a media echo chamber. His supporters live in what she calls a “parallel universe” filled with alarmist conspiracies and revisionist histories. In this world, the country’s military dictatorship, which ruled from 1964 to 1985, is remembered for order and progress rather than terror.

Meet

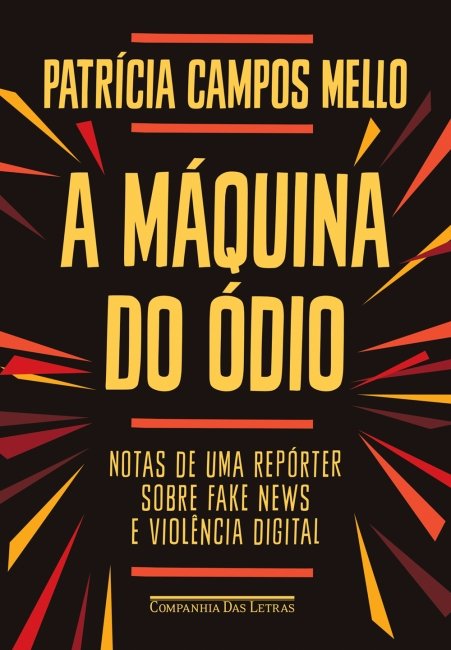

Patrícia Campos Mello is a reporter and columnist for Folha de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s largest newspapers. She studied journalism at the University of São Paulo and earned a master’s in economic reporting from New York University. She has reported from more than 50 countries on human rights, public health, business, international relations and more. Campos Mello is the 2020 recipient of the Maria Moors Cabot Award from the Columbia Journalism School, where she is a research fellow. In 2019, she won the International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists. Her new book is A máquina do ódio: notas de uma repórter sobre fake news e violência digital (or, “the hate machine: notes from a reporter on fake news and digital violence.”) Follow her on Twitter at @camposmello.

In A máquina do ódio, Campos Mello explores how Bolsonaro’s political machine targets journalists and government institutions.

Her reporting in 2018 and 2019 on WhatsApp mass messaging — used by Bolsonaro and his Partido Liberal to skirt campaign finance laws — helped lead the judiciary to implement tighter social media regulations in this election cycle.

Campos Mello successfully sued Bolsonaro over spurious claims he made, accusing her of exchanging sex for her stories. But she continues to face legal harassment from the president’s powerful allies and abuse from his supporters. Read her recent column in The New York Times about Bolsonaro’s “troll army.”

How’s your Portuguese? You can also read this 2020 column in Folha, where Campos Mello argues that simply being a woman puts her and her female colleagues at risk of personal attacks. These attacks, she says, have nothing to do with their reporting — but undermine their work by intimidation.

In a Pointer investigation published in May, Campos Mello looked at how Bolsonaro, Google and Facebook constituted an “unholy coalition” that block measures intended to cut back on the spread of disinformation.

Campos Mello has reported from conflict zones around the around, including Libya, Iraq and Syria. Her 2017 book Lua de mel em Kobane (“honeymoon in Kobane”) tells the unlikely love story of two Syrians living in the grip of the Islamic State.

Last year she wrote about a several Brazilian people and groups included on a U.S. international terrorism watchlist. One man on the list, she found, was the director of an NGO that resettles Syrian refugees in Brazil; he accused U.S. officials of having a “Hollywood imagination.”

Brazil’s former foreign minister convinced the government to purchase hydroxychloroquine, despite the drug’s ineffectiveness against covid, Campos Mello reports. Her work notes that only in Brazil, India and the United States has politics fueled covid misinformation.

Learn

Linguists Marluce Pereira da Silva and Cid Augusto da Escóssia Rosado say attacks on female journalists with sexualized language and inuendo are indicators of Brazil’s “democratic fragility.”

Bolsonaro has used extremist rhetoric to energize his base, imploring supporters to buy guns in the runup to the election. Thanks to new executive orders on guns that he signed during his term in office, more of them can do that.

As he voted in the first round on Oct. 2, Bolsonaro told Brazilians they should be suspicious of any result that doesn’t have him winning the election with “at least 60 percent” of the vote.

In the final months of the race, military leaders raised the stakes by suggesting, like Bolsonaro, that the country’s voting systems are vulnerable. There is now serious concern that, should he reject the Oct. 30 outcome, Brazil may see another coup.

Writing for Vox, reporter Ellen Ioanes considers just how badly a Bolsonaro loss might turn out. She finds that concerns over a military takeover are justified — to a point.

Whether Bolsonaro challenges the results or not, the long-term consequences of his scorched-earth politics are serious. According to Gallup, two thirds of Brazilians lack confidence in the integrity of their elections.

During a gathering of defense ministers from around the Americas, in July, Brazilian officials assured Lloyd Austin, the U.S. secretary of defense, that they would ensure security in the electoral process. Nearly 60 years ago, American leaders supported the 1964 coup.

Despite improvements in Brazil’s election laws, including an ostensible ban on disinformation, Facebook has failed to adequately police fake news, according to an investigation by the international advocacy group Global Witness.

After da Silva served time in prison on corruption charges, Brazil’s supreme court threw out his conviction, enabling a remarkable comeback for a politician who once enjoyed approval ratings as high as 80 percent.

Watch him speak to supporters on election night, after learning his campaign would have to go on for another month.

Despite all the noise in this election, there hasn’t been a lot of intelligible sound from either camp on major issues facing the country and the world. Especially troubling is the growing ecological catastrophe in the Amazon. Bolsonaro’s policies have accelerated deforestation and supported gold mining, which often targets indigenous lands.

And, of course, there’s the economy and Brazil’s trenchant inequality. After flying high in the early 21st century, the Brazilian economy collapsed in 2014 and has been limping along ever since. The Financial Times offers this breakdown on the nominees’ alternative visions for prosperity.