Rights of Passage

The United States has a checkered past when it comes to welcoming new Americans.

Read

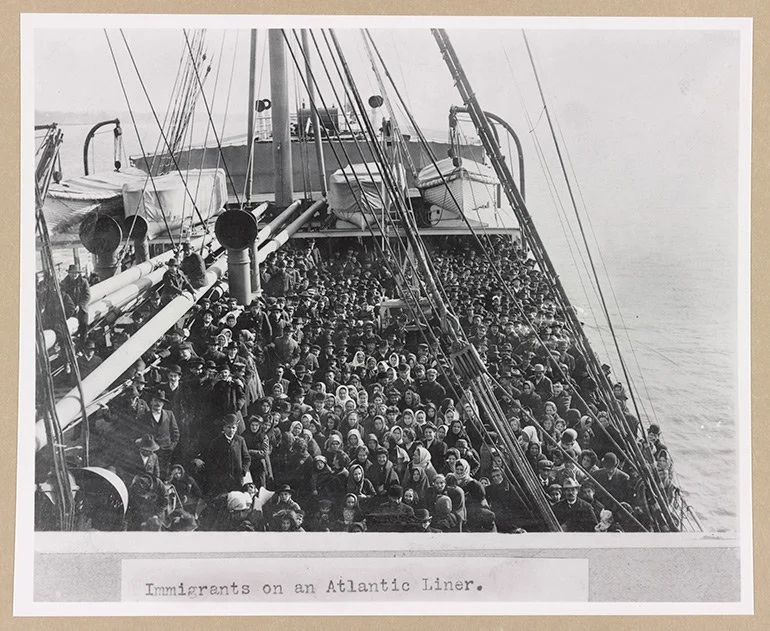

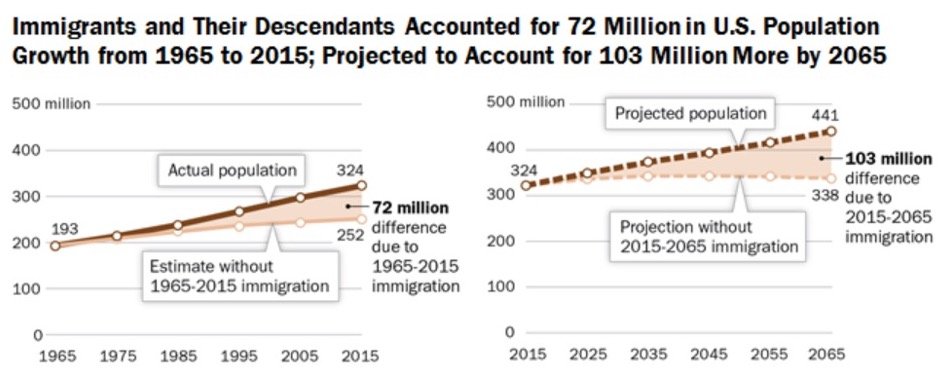

As many as a quarter of Americans are foreign-born or the children of immigrants. Since the country’s founding, newcomers have made and remade the United States every generation. And yet debates about immigration policy are deeply fraught, highly cyclical, and often coded in racial animus, says legal scholar Amanda Frost. America’s pathways to citizenship have gotten narrower in recent years, even as they face constant fire. It’s a problem, she argues, that political leaders shouldn’t ignore.

As Frost explains, the Declaration of Independence itself was pro-immigration, and helped established the United States as a haven for those seeking freedom and opportunity. What’s happened since then? A lot of ping-pong as it turns out, for often ugly reasons — beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. More recently, the lack of any real, comprehensive immigration reform since 1965 has led to dangerous humanitarian conditions at the southern border and many political contradictions.

While the future of immigration law is uncertain, Frost finds reason to hope that America will return before long to its once proud embrace of new citizens. In debunking myths about the dangers of too much immigration from “undesirable” places, she points to the vibrancy of immigrant communities, their contributions to the country’s economy, and the fear-mongering of the past that has proved so absurd time and again.

Meet

Amanda Frost is the John A. Ewald Jr. Research Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. She has been a visiting scholar at Harvard University, the University of California–Los Angeles and the Université Paris Nanterre, among others. Her work focuses on immigration, citizenship and federal law. Frost contributes frequently to the Atlantic, New York Times and Washington Post. Her most recent book is You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers (Beacon Press, 2022), which explores the circumstances in which civil rights have been taken away from people throughout U.S. history. Follow her on Twitter @amanda_frost1.

In You Are Not American, Frost recounts the stories of many U.S. citizens who have had their legal status questioned and even stripped because of their race or ethnicity, their choices in marriage or their political activism.

Read more about one such figure, Kim Wong Ark, whose troubles continued even after his landmark U.S. Supreme Court case affirmed birthright citizenship in 1898. We spoke with Frost about that history, and more, in Season Two.

Frost’s next book, Born in the U.S.A.: Birthright Citizenship and the Making of America, is due out later this year.

In 2020, when the federal courts were considering whether noncitizens should be counted in the census for the purpose of apportioning House seats, Frost weighed in, in this Atlantic essay. The usual practice of counting noncitizens remains the law of the land.

Last year, Frost warned that Republican leaders risked political consequences for resisting a pathway to naturalization for America’s 11 million unauthorized residents. It would only drive more new citizens to vote Democratic, she argued.

Want to learn more about how the framers viewed immigration? Writing in the Southern California Law Review, Frost discusses their views and the clause of the Declaration of Independence that chastises King George for making it harder for people to migrate to America.

Learn

Not all leaders in the early republic were pro-immigration. While Thomas Jefferson supported unlimited immigration — for political reasons as much as anything else — his Federalist nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, did not. Though himself an immigrant, Hamilton was worried about the French having too much influence.

Benjamin Franklin, meanwhile, had concerns about the Germans being able to integrate fully in the life of the new nation.

George Washington, on the other hand, repeatedly invoked America’s promise as a refuge for the persecuted. So where does that leave us? Historians tend to warn against reading too much into any of this rhetoric from another era.

Today, more than 40 million people in the United States were foreign-born — the highest immigrant numbers of any country. Immigrants and their children, i.e., first generation Americans, account for some 25 percent of the country’s total population.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services has been the locus of political football in recent years. The Biden administration last year replaced (once again) the agency’s mission statement, which under President Trump had ditched the idea that America is “a nation of immigrants.”

President Biden has also directed customs and border officials to replace their uses of the word “alien” with more neutral terms such as “noncitizen.”

In the latest twist for the Obama-era policy of providing a provisional legal status for undocumented children brought to the United States, a federal appeals court agreed that the program as adopted violated federal law.

Still, it ordered a lower court in Texas to decide whether regulatory changes under Biden might effectively save the policy — known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. For now, the status of current DACA recipients is still operative.

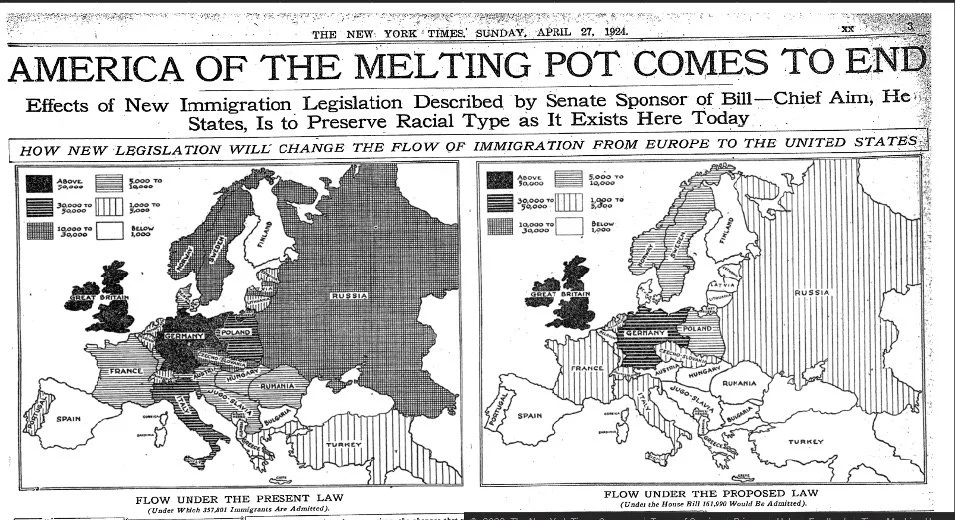

This kind of back-and-forth on immigration policy is nothing new. While a 1924 law codified strict quotas based on fears of nonwhite immigrants, another, in 1965, set the stage for an era of more welcoming procedures — and changed the face of the country in the process.

If you want to go really deep on immigration law and history, Frost recommends a number of excellent books: Americans in Waiting, by Hiroshi Motomura; The Walls Within, by Sarah Coleman; Deportation Nation, by Daniel Kanstroom; Impossible Subjects, by Mae M. Ngai; and America for Americans, by Erika Lee.

Lee, incidentally, joined us on the show in our first season, to talk about the sordid history of xenophobia in the United States.

As our listeners know, immigration is an important subject for Democracy in Danger, since a fundamental question for government by the people is who gets included in the demos. Recently, we’ve also covered the criminalization of unauthorized migrants and America’s complex asylum practices.